Nobody wants to come across as pedantic, but if you want the truth - read on!

1. Yes, if you are from Berlin, you are a Berliner, New York = New Yorker, Hamburg = Hamburger, Braunschweig = Braunschweiger, Frankfurt = Frankfurter, Limburg = Limburger, Vienna i.e. Wien = Wiener, etc.)

2. Yes, there are donuts called "Berliner."

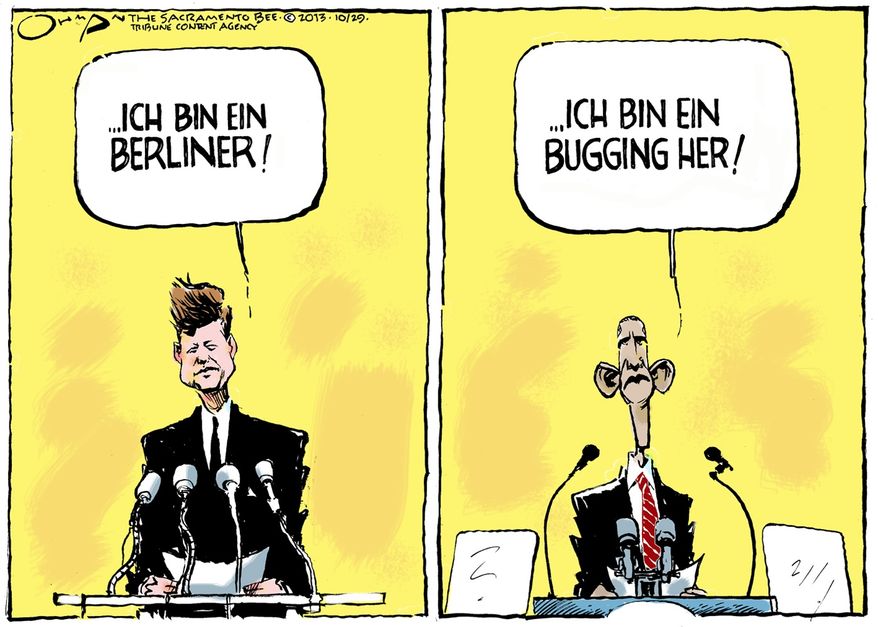

3. Did JFK say "I'm a jelly donut?" No

Two thousand years ago the proudest boast was "civis Romanus sum." Today, in the world of freedom, the proudest boast is "Ich bin ein Berliner."I appreciate my interpreter translating my German! (JFK also practiced in front of Mayor Willi Brandt)

All free men, wherever they may live, are citizens of Berlin, and, therefore, as a free man, I take pride in the words "Ich bin ein Berliner!" (JFK phonetically wrote it out below as "ish bin ein Bearleener" and did prettty well to pronounce it as such.)

RESPONSE: From the Atlantic: "Afterward it would be suggested that Kennedy had got the translation wrong—that by using the article ein before the word Berliner, he had mistakenly called himself a jelly doughnut. In fact, Kennedy was correct. To state Ich bin Berliner would have suggested being born in Berlin, whereas adding the word ein implied being a Berliner in spirit. His audience understood that he meant to show his solidarity."

RESPONSE: From the excellent Urban Legends Page at about.com - worth reading

An actual Berliner would say, in proper German, "Ich bin Berliner." But that wouldn't have been the right phrase for Kennedy to use. The addition of the indefinite article "ein" is required, explains (authority Prof. Jürgen) Eichhoff, to express a metaphorical identification between subject and predicate, otherwise the speaker could be taken to say he is literally a citizen of Berlin, which was obviously not Kennedy's intention.

To give another example, the German sentences "Er ist Politiker" and "Er ist ein Politiker" both mean "He is a politician," but they're understood by German speakers as different statements with different meanings. The first means, more exactly, "He is (literally) a politician." The second means "He is (like) a politician." You would say of Barack Obama, for example, "Er ist Politiker." But you would say of an organizationally astute coworker, "Er ist ein Politiker."

RESPONSE: If you'd rather watch a quick Youtube video from Rewboss - covered thoroughly and with humor. Origins as well.

RESPONSE : There are three main points (lengthier explanation here)

1. Berliners obviously did not misunderstand JFK. They cheered (video) rather than laughing.

:origin()/pre03/d795/th/pre/f/2010/008/3/5/ich_bin_ein_berliner_by_clazziquai.png)

3. You leave out the article (ein = a) when you are talking about actual provenance

or profession, you use the article when you are referring to someone as

having character traits of a certain profession/nation. Thus, you could

say "Dem kannst du nichts glauben, das ist ein richtiger Schauspieler"

where you are not saying that the person in question is earning his

living on the stage, but that this person knows how to play on his

audience's emotions.

General note: This is one of the most useless rules to torture students

with and also confuses them about 2 nominatives surrounding the forms of

"sein". There are plenty of regions (Bavaria, for example) where the

"ein" is extremely common. There are plenty of "jobs" which are not

really careers. You will usually arouse mirth among Germans if you say of

someone "Er/sie ist Dieb/in" (He is a thief - it's not his occupation!). The use or no use of the article is not

worth wasting more than 30 seconds on in the first three or four years of

language instruction (i.e. point out to the students that in standard

German one usually does not use the article with nouns denoting natinal

origin, profession or religion, but that it's OK to do so). In later

years, one might give it some instructional thought, but one should make

sure that the examples one teaches end up being correct.

Eckhard Kuhn-Osius - author of the authoritative published article

"Ich bin ein Berliner": A History and a Linguistic Clarification

RESPONSE : On a personal note, a friend of mine was a university student in Berlin at the time of Kennedy's address. I asked him about the double meaning of "Berliner", and he gave me an incredulous look. He felt that EIN Berliner was correct, that "Ich bin Berliner" would have sounded as if Kennedy were actually a citizen of Berlin. The EIN added an emphasis needed for his figurative use of BERLINER. My friend then added that he could assure me that no one in that crowd, at that time, would have misunderstood Kennedy's words. Hank Schwab

RESPONSE : The article referred to is: Eichhoff, Jürgen: '"Ich bin ein Berliner": a History and a Linguistic Clarification', Monatshefte 85 (1993), 71-80. It demonstrates that Kennedy did not make a mistake and was not misunderstood. In a previous post, I cited numerous literary examples of the use of ein with nationality or profession (ich bin ein Preusse; er ist ein Bauer). There are sometimes stylistic reasons for the one or the other (with or without the ein), but the elementary fact that seems hard to learn is that 'ich bin ein Berliner/ Bauer/etc.' are not incorrect, and are quite common.

The base cause of this misconception is the inability to realize that the grammar rules we learn are almost always falsifying oversimplifications. If we have learned 'you don't use the indefinite article with nationality or profession', that is exactly such a false rule. Properly stated, it should be 'you usually don't use etc.' Joseph Wilson

RESPONSE: How did it all begin? FAKE NEWS from the NYT in 1983! CNN also perpetuated the myth at one point.

RESPONSE : Further to Joe W's message, I want to add that using these words without an article sounds more technical, purely informative. When the article is added, the word seems to gain an extra dimension, communicating more than a simple fact. There seems to be added emotion, personal emphasis or involvement. "Ich liebe die See. Ich bin eine Hamburgerin." (the "eine" providing emphasis: "After all, I'm from Hamburg.")